The scrambalisation era is here

Nick Bisley, Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences and Professor of International Relations at La Trobe University

2025-04-16

TRADE AND ECONOMICS

This article first appeared on The Interpreter, published by the Lowy Institute

Unsurprisingly, many commentators declared 2 April 2025 as the day “globalisation” died. Donald Trump’s “liberation day”, jacking up of barriers to the US market to their highest levels in nearly a century, signalled the end of an eight-decade commitment to free trade. But in truth, the era of globalisation ended in Trump’s first term, in March 2020, as Covid swept the world. Trump’s historic act of self-harm this month instead marks a first major step into a new reality.

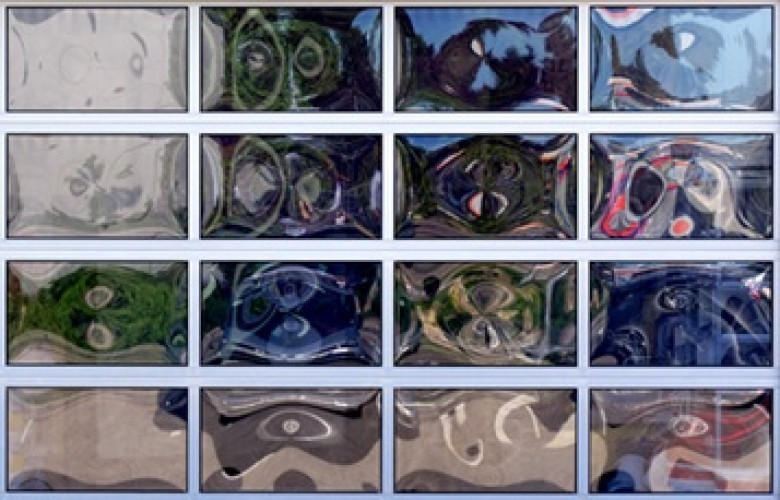

Welcome to the era of “scrambalisation”. This ugly mishmash of a label captures the disfiguring of the global economy that has occurred in the years after the pandemic, a strange hybrid of old and new.

In the years between the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the declaration of the Covid pandemic, globalisation was the defining feature of the world economy. Markets and firms were let loose, with price and efficiency seen as the best determinants of what was made where and at what cost.

Globalisation was an astonishing engine of growth. The process was instrumental to the dramatic economic expansion in Asia and beyond. The downsides came with the dislocation of traditional patterns of manufacturing and employment as well as important social consequences. Large gaps opened between the most affluent and the less well off. Shifts in the global balance of power also tore the cultural fabric of many societies. But a broad consensus saw the benefits – indeed for some, the inevitability – of giving markets free rein.

The pandemic saw it all crash down. The vulnerabilities of globalisation suddenly became unbearable. From the inability to make personal protective equipment and pharmaceuticals, through to the snarling of supply chains, the global economy seized up. Suddenly the world realised that supposedly finely calibrated systems of production and distribution had major problems. The pandemic empowered political leaders to remember the forgotten power of states over markets.

So, if the pandemic years marked the end of an era when markets ruled the world, what would follow next was less clear. Would the old ways of doing things snap back into place, with perhaps a “small yard, high fence” attitude to ensuring sovereign capability in niche areas of sensitivity? Or would the strategic tensions that had accelerated during the pandemic years lead to a reversion to Cold War style blocs?

Trump’s tariffs signal a future that will be badly scrambled. The distortionary impact of political second-guessing in investment and trade dynamics will be felt across the globe. Some markets are likely to remain free of interference, particularly commodity trade, goods of low complexity, and some services. But a chasm between the United States and China will hinder the old way of doing things. Many sectors will be overrun by regulations and rules, tax breaks and subsidies. These began with high technology and “critical sectors” and now extend to the high tariff walls between the United States and China.

Scrambalisation will mean that the global economy is badly distorted by the larger dynamics of geopolitical competition. Supply chains in some areas will come to resemble the security alignments of key regions. The distortion will also be felt in distinctive national priorities and national champions given special protection by governments. This will include car manufacturing, ships, industrial machinery or consumer durables including household appliances (think toasters). It will extend to a range of other sectors that include some high technology or those that play a key role in the production of supply chains.

Growth rates are likely to be depressed by the significant brake that this applies to the global economy. And most worryingly, emerging economies will suffer as they find themselves locked out, inadvertently, of many market opportunities.

The era of scrambalisation will be as ugly as the word.

Membership

NZIIA membership is open to anyone interested in understanding the importance of global affairs to the political and economic well-being of New Zealand.